WHAT A EURPEAN HAS SEEN IN KURDISTAN

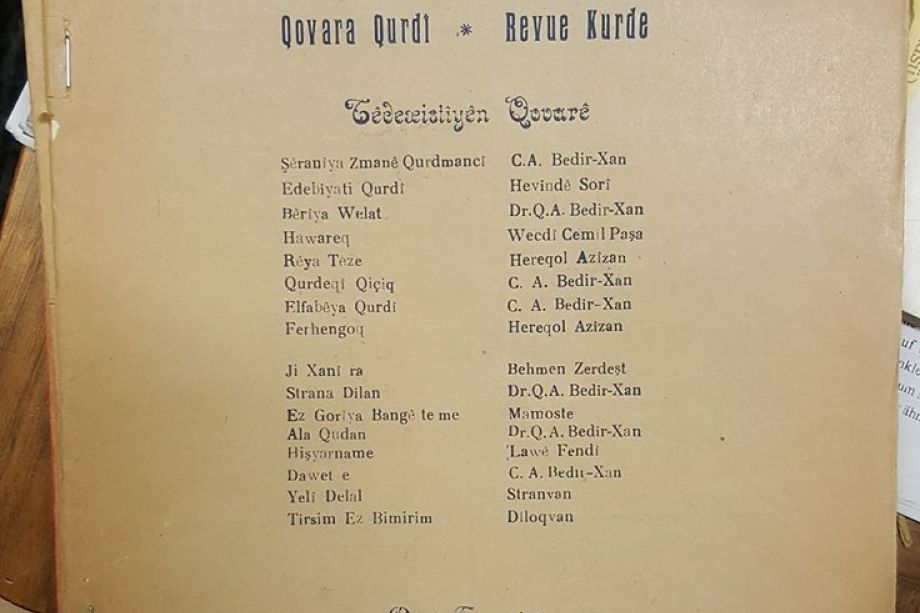

Herekol Ezîzan is a nom de plume for Celadet Ali Bedirkhan. Celadet was born in 1893 in Istanbul and died in 1951 in Syria. He had a Masters Degree in Law from Istanbul University and he finished his studies in Munich. He spoke several languages: Arabic, Kurdish, Russian, German, Turkish, Persian and French. In 1932 he published the journal HAWAR in Damascus. HAWAR constitutes the foundation of the modern Kurdish literature. HAWAR founded the Kurdish grammar; everyone who writes in Kurdish, Kurmanji, are aware of and follow HAWAR’s writing rules. In addition, Celadet Ali Bedirkhan left behind around ten valuable books in different genres.

The other day an acquaintance said to me:

– Don’t you know that a European journalist who has travelled to Kurdistan now is in Damascus?

My acquaintance told me more about the European journalist, but he did not tell me where he lived. After having visited several boarding houses in Damascus I met him.

– HAWAR? Yes, when I was in Kurdistan, there were some people who told me that there was a journal called HAWAR that was published in Syria. I would really like to see that journal.

I had brought a few issues of HAWAR and gave them to him. He looked into them, leafed through them and said:

– You want to ask me a few things about your country, don’t you? I also have some questions I would really want to ask you. Your first question is perhaps what I have seen in Kurdistan?

– Yes, exactly.

– What I have seen of what the Turks have done to the Kurds only you and the ones I have met know, but a European would not believe it. I have seen horrible scenes.

– The government in Ankara does not let foreigners into Kurdistan, especially not journalists. How did you manage to get there?

– You are right, and it’s not only foreigners that they don’t allow to come in, the locals cannot move freely without permits from the Home Office. But I did not say that I was a journalist and I have some old countrymen who have been there for a long time. Thanks to them I could get into Kurdistan, however, not entirely without difficulties. I stayed there for six months. You cannot imagine how I suffered during that half year. The Turks in power don’t have any humanity left in them.

We lived in “…”. Sometimes I left the town and went east, wandered through the villages and their different clans. In spite of that, I have not got so far as to the border regions. But our friends who have been there told me that the atrocities there are worse than those that happened before our eyes. Everything I saw in Turkey I have written down in my notebook. When I return to my country, I will write articles and publish a book.

It happened several times that the military made raids into the villages that I had visited and they took all the men with them. These men never came back.

One day I saw something that I will never forget. We went on foot between the villages. We met an old Kurd, between fifty and sixty years old. A twenty year old Turkish soldier showed up in the brush. The elderly man had a two year old child in his arms. The soldier swore at him and hit him in the face with a billy club. The man’s face was injured and the child’s head was crushed. The man held out his head because he wanted to protect the child. At last the soldier got tired of it and stopped. The man raised his head. We thought he was crying, anyone would think that. No, he did not cry. He turned his face towards the sky, then he looked at the soldier and smiled. Yes, it was terrible.

There was a village we visited quite often. There we had a friend, a very old Kurd, one hundred and two years old. I don’t know why we had not visited the village for a while. We missed our friend. One day we three friends decided to go there and visit him. Our old friend was healthy and alert. He still had his teeth in shape. He could eat everything and he was always funny and happy. He was joyful when we visited him. But this time we noticed that something had changed; he could not stand up from where he was sitting and come and meet us. He wanted to, but his legs would not carry him, they were swollen. We wondered what had happened. He said:

– Fifteen days ago the military came to the village. They were looking for weapons. We did not have any weapons, we didn’t even have a knife. They tied all the young men together and took them with them. You can probably guess that these young men never returned either. Now it was my turn, they said I had hidden a rifle. No, I pleaded, I have not hidden any weapon. They didn’t care about what I said, they threw me to the ground and hit me hard with billy clubs. My leg was bleeding, they didn’t care. I felt sick and fainted. They left me lying there and went away. After that I have had problems getting up, and I just lie here. You have to excuse me for not being able to get up and come to meet you.

We asked him why they had beaten him in that way.

– Because I’m a Kurd, he said.

Then he fell silent and still, he looked anxiously around himself and said:

– No, I’m wrong. I used to be a Kurd. Now I am a Turk. We are all Turks in this country.

The poor man was still afraid and we noticed that he was also suspicious towards us. Have you ever seen or heard such stories? To beat and humiliate an old man with a two year old child in his arms and to torture a man who is over a hundred years old? How can a man raise his hand towards such people?

It is not enough? I don’t know what else I can tell you. A country that has such a constitution. Let me say this in Turkish: “The Turks are the biggest nation, all who live in Turkey are Turks, here there are no other nations or languages.”

Make note of the fact that Turkey cannot exist for long in this way. It is not without a reason that I say these words. I went to Istanbul and saw their situation there too. They have elevated themselves so high that they no longer can stand up, they have to fall.

After this report he asked me some questions and wrote in his notebook. Then we shook hands and parted. Because he wanted to remain anonymous while he was here I cannot reveal his name. But when he returns to his country and publishes his texts, we will also read his texts in HAWAR and we will also know his name.

HAWAR, 1933, Damascus