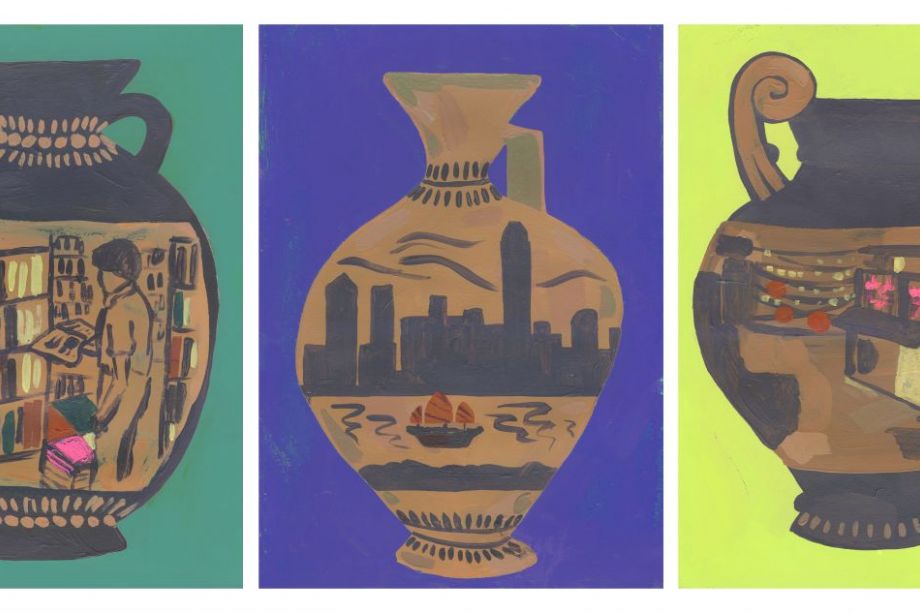

Hong Kong is my Myth and my Legend

Yan Lianke is one of China’s foremost authors. His recent texts have become more critical of society, which has made it harder to get them published. His works have either been retracted or not re-published. In this text Yan Lianke describes his relationship with Hong Kong—this familiarly strange and strangely familiar place. To him Hong Kong remains a myth—a distant fairy-tale place that never becomes a reality.

My impression of Hong Kong when I was young resembled my impression of Ancient Greece as a teen—its myths were like the wind in our family’s fields, which you could always hear blowing in your ear or roaring overhead. This was true until 1994, when I was roundly criticized for the novella Summer Sunset, as a result of which I had to write self-criticisms every day, leaving me so busy that when it was time to eat I couldn’t even find my table or my chopsticks. At that point, it began to seem as though perhaps Hong Kong wasn’t so far away after all. The reason why Summer Sunset was criticized is because an issue of the Hong Kong journal Cheng Ming happened to say some good things about me in relation to Summer Sunset, describing me as “a leading figure in mainland China’s fourth-wave military literature movement” and someone who “describes military figures’ spiritual decadence”. The novella was therefore banned, placing me in critical jeopardy and making it necessary for me to repeatedly offer self-criticisms. This portentous incident proved Mao Zedong’s observation that “everything our enemies support, we will oppose; and everything our enemies oppose, we will support,” and after this, my fate became inextricably linked with that of Hong Kong.

1997 was a historic time that energized the people of mainland China. Because I heard countless songs celebrating the handover, I always assumed that after 1 July we would enter a new phase of having more money than we could possibly spend—like opening a sluice and allowing a torrent of water to flood unimpeded into the mainland. Given that this canal was already opened, why wouldn’t our family’s boat also be lifted by the same rising tide?

I therefore responded enthusiastically to the summons, and proceeded to invest my entire life savings in the bull market.

After 1 July, however, our family, which had only recently become relatively well-off, lost everything, and we were once again reduced to poverty.

In 2004, as a result of the publication of the novel Lenin’s Kisses, I was interviewed by Hong Kong’s Phoenix Television. The interview was broadcast the following day, as a result of which, just minutes after I showed up for work, I received a solemn yet amiable notice ‘inviting’ me to leave my position working for the army. Although at that point Hong Kongers viewed Phoenix Television as being rather ‘out there’, in China we still regarded it as being very much ‘here’.

In 2005, the appearance of Serve the People! was a catastrophe for me and the literary field. It was Hong Kong journal Asia Week that first reported this incident, and it was also the quick-footed Hong Kong press that first sent Serve the People! out to bookstores and to the world. It was only much later that I finally saw the book with my own eyes, and I was so terrified by the book’s cover design and cover image that I felt as though I were being strangled. At the same time, however, another suspicion flashed through my mind:

“Perhaps it is true that Hong Kong—like the streets, plazas, and marketplaces of Ancient Greece—is in fact a place where writers can freely argue and philosophers can debate.”

In 2007, when I went to the City University of Hong Kong for a conference, the first thing I did when I got out into the city was run over to look at the spectacular array of small bookshops in Hong Kong’s Central district. I leafed through the free newspapers and the countless periodicals, books, and pictorials that were arrayed on display racks in the entrance to each shop—like a starving person suddenly finding himself in a supermarket surrounded by free food and drinks. Although I could neither believe nor explain it, I felt that I really did experience what the streets and markets of Ancient Greece must have been like, where anyone could argue and debate as they wished. To tell the truth, coming from North China’s Loess Plateau region, I was not particularly impressed with Hong Kong’s chopstick-like skyscrapers. In fact, far more than the dazzling clothing and the luxury goods displayed behind the glass counters, and the bars of Victoria Harbor and Lan Kwai Fong, what truly impressed me were the streets full of journals and books, which theoretically anyone could write, publish, and read. At that time, after I took a new issue of Cheng Ming from a magazine rack in front of a bookshop, I became filled with regret and found myself at a loss for words. It was as if someone who had just spent an eternity in prison or wandering through a war zone suddenly finds himself standing in the streets of a bustling city. Although the former prisoner knows that the person who sent him to prison must be somewhere in these crowded streets, do any of these people or streets have any direct connection with his having been jailed? Similarly, although the war zone was full of tanks, rubble, and mangled corpses, the city is nevertheless full of lights, excitement, and people enjoying peace and prosperity.

I proceeded to browse that copy of Cheng Ming for a long time in a corner of the store, until eventually I put it down and walked out.

I walked through the streets of Hong Kong’s Central district.

I walked through Hong Kong’s buildings and crowds.

I didn’t feel a trace of resentment, jealousy, or envy. It was as though I knew the beauty of Athens, but also realized that this Athens bore no relationship to the one we associate with Ancient Greece. A few years later, I went to Hong Kong Baptist University to serve as a resident writer, and then visited Hong Kong University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong to chat under the pretext of giving a lecture. Finally, I ended up teaching at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. It feels as though time has passed like the wind, blowing me into the fields and into the past, into myths and legends. In Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, which appear far but are in fact quite near, and here in Clear Water Bay, which is forever at my side, the people, wind, ocean, learning, orderliness, and the fleeting yet meaningful history and reality—all of this strikes me as both familiarly strange and strangely familiar. At the same time, this setting has become the Ancient Greek myths and legends of my destiny.

Teaching, strolling, reflecting, and writing—every day I go down to the sea shore to walk and look around. As I am walking and looking, I sometimes suddenly feel anxious and insecure. I gaze out at the ocean and the sky, and wonder whether a climate-driven rise in sea level may result in the disappearance of this island. Given that Hong Kong has already become part of my fate, if it were to disappear, then where would my myths and legends drift to, where would they alight, and where could they survive?

----

Yan Lianke who resides in Beijing is one of China’s most well-established and acclaimed authors. Yan Lianke’s career began in 1978 and he has since published several novels. Most of his books have been banned in China. He is currently Professor of Comparative Literature at the Renmin University of China in Beijing.